by Chris Horst | Jul 29, 2015 | Blog |

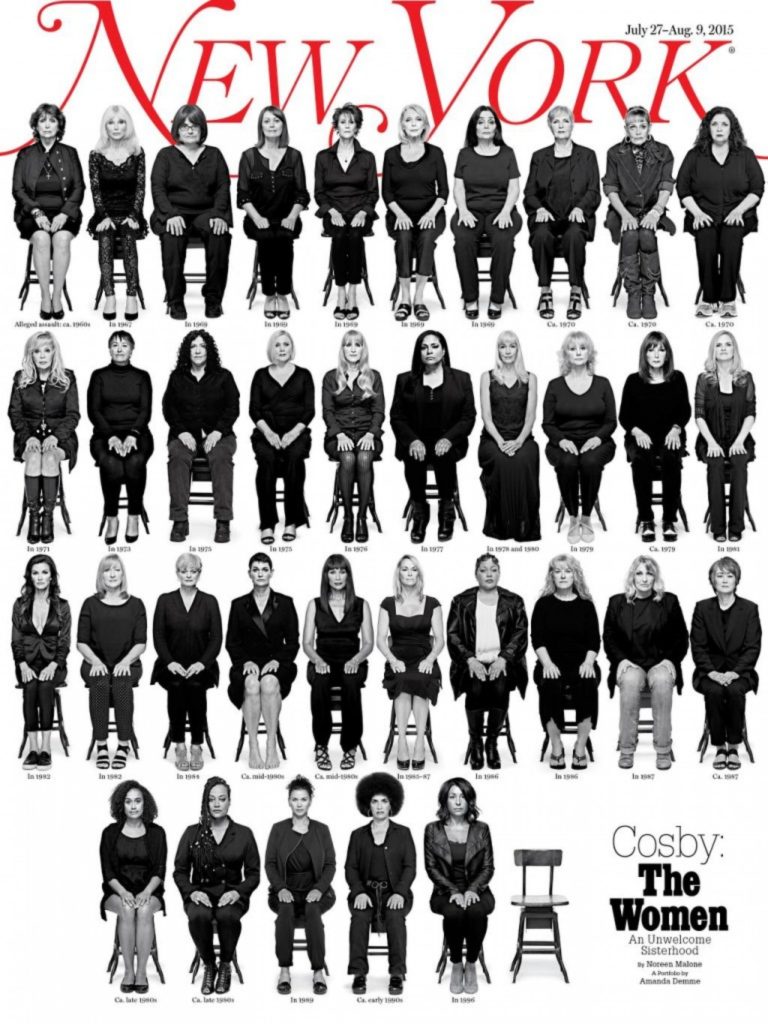

The cover image that took down a giant.

That’s how I see it. This week, New York Magazine published a cover of 35 brave women (warning: explicit content), all of whom share one tragic event in common: Each woman was sexually assaulted by Bill Cosby. In one beautiful image of solidarity, these 35 women did what none of them could do on their own. They stood together in united witness against abuse and violence.

Bill Cosby still walks our streets a free man. But, in the long battle to make known his formulaic victimization of women, the cover image is a fatal blow. He may never see a literal jail cell, but he will live the chains of isolation he has created for himself. Unless he admits his wrongs, repents, and suffers the consequences of these wrongs, Cosby will remain free only in the legal sense. No longer will the world believe “his side” of the story. The 35 women present a shared account that silences the posturing and explain-it-away-stories Cosby concocts.

In Playing God, Andy Crouch writes, “Here is what we need to discover about power: it is both better and worse than we could imagine.”

When Cosby lured, drugged and raped young women, he demonstrated just how terribly power can be used. His power afforded him the opportunities to commit these crimes, and his power prevented these victims from having any recourse. He was too wealthy, too well loved, and too famous for the powerless to fight back. Or so it seemed.

But in the New York Magazine image, we also see power at its very best. What one woman could not do alone, many women can do together. In community, they stood up for orthodoxy, fighting for what is true, right and just.

And, in a small farming town in south Asia, another group of women is rolling back injustices in their community.

Shanti is joined by ten women in a savings group. They have elected her president and have been together as a group for over two years. During that time, they have helped one another financially. As they’ve saved together, their shared bank account has grown from very little to over $500 today. They’ve helped each other start and grow small businesses. They’ve helped one another with medical fees and school bills. The group even made Shanti an $80 loan to help her start a grocery store.

But more valuable than loans or savings accounts was the newfound power this group of women had together. In their village, “society’s look toward woman is very backward,” Shanti lamented.

Many of the women in her group experienced this backwardness. When they gathered together each week in a local church, they shared their stories—their joys and pains. Several women in the group shared that their husbands regularly would abuse them physically.

“I always felt that as a single person,” Shanti said, “I wouldn’t be able to accomplish anything. But as a group, we can do a lot. So that’s what I did. I mobilized our whole group to get involved and make use of our unity.”

When one woman shared she had been abused, the whole group would go and name the offense and confront the abuser, warning him that they would call the police if it happened again. The results are encouraging.

“The community has realized our unity and the power in it,” said Shanti. “It’s changed our whole outlook on life. It’s given us confidence that we can do anything as a united group.”

Shanti’s group hasn’t stopped at confronting domestic abuse. They’ve chased out a bootlegger in their community. They’ve pressured a local councilwoman to make good on her promise to clean up the sewer system. And they are keeping their sights set how they can together make their community better.

Like the 35 women victimized by Bill Cosby, these women created power they did not have on their own. Both groups practiced a sort of “beautiful orthodoxy”—a powerful phrase coined by my friends at Christianity Today. Beautiful orthodoxy is perhaps a counterintuitive pairing. Holding truth and kindness in tension is terribly difficult. But it’s also the most powerful, as evidenced by the actions of these two groups of women.

Their message is orthodox. They spoke truth to abusive power. It affirms what is right and exposes what is wrong. And, the ways both these groups of women have communicated this truth is beautiful. They made their statement in solidarity. In unity. A posture modeled first in the Trinity and again-and-again throughout scripture.

Joan Tarshis, one of Cosby’s victims, called her group of 35 a “sorrowful sisterhood.” Chelan Lasha, a fellow victim, said she’s “no longer afraid.” She said she feels “more powerful” together with this group. Shanti said she no longer feels she is without power. These restorative actions of beautiful orthodoxy do not undo the pain. But they do create a more just future. They embody the ancient proverb from Ecclesiastes: “And though a man might prevail against one who is alone, two will withstand him—a threefold cord is not quickly broken.”

![Change in the Age of Shallows]()

by Chris Horst | Nov 8, 2012 | Blog |

My attention span isn’t what it used to be. While reading a terrific book last night, I noticed my itchiness for the end of the chapter. It felt forever away. The chapter ran thirteen pages. In 2012, apparently, thirteen pages is my new eternity.

Maybe you can relate: The moment you wish a 90-second YouTube video would get to the point. The moment you yearn for a red light so you can catch up on email. The moment you need to check a new text message during dinner with friends. This growing impatience dangerously impedes our ability to stick with things that matter.

I’m sure some teenage whippersnapper will suggest I’m simply recreating the tendency of our grandparents to overstate the distance they walked to school. They didn’t walk uphill both ways, always in blizzard conditions.

But our attention spans are slipping. According to a new book, our physical brains have adapted to our shared shiny rock syndrome. In The Shallows, author Nicholas Carr argues we have lost the ability to last. We skim and scan, but rarely sustain. While debate remains whether our brains have physiologically changed in the digital age, my experience certainly affirms Carr’s thesis. Maybe it’s my world-in-my-hand smartphone. Or, maybe I subconsciously yearn for the days when my dad’s car phone was a connectedness marvel. No matter the reason, I’m itchier than I was five years ago.

I wonder how our multitasking influences how we view change within people. Even Desmond, my two year old, rapidly switches between apps on my iPhone (…and no, parental purists, I’m not too proud to admit he borrows it at restaurants). I mean, goodness, he gets unruly halfway through Goodnight Moon.

Does the age of shallows stunt our patience? On a recent trip to India, I walked through a “slum among slums.” Conditions were abysmal, and I craved a “fix and flip” solution to the wrenching problems. I questioned whether I had the endurance to invest in the sort of change that demands time. I questioned whether my millennial sensibilities would allow for the sort of steady and faithful life-on-life investment needed for true growth.

We need to recalibrate to a longer view. Bangladesh cut infant mortality by two thirds and more than doubled female literacy over the past twenty years. The “rise of globalization and the spread of capitalism” halved extreme poverty worldwide over the same time. The Church spreads at unprecedented rates south of the equator. It’s not instant, but it is remarkable.

We need a personal recalibration too. Good change is rarely immediate. Friendships demand TLC. Marital harmony is more like a slow cooker than a microwave. A virtuous life is not “acquired spontaneously” but rather a “product of long-term training, developed through practice.” Desmond didn’t master the barnyard animal puzzle overnight. These good things demand the long view, but the Information Age clouds us from seeing it.

Change takes time. In a broadband world, Indian slums prompt frustration with the measured pace of change. But in the case of a wayward sibling or a forlorn slum, slow can be good. The knight on his white horse creates a scene, but he doesn’t change anything. Hitting the jackpot makes waves, not change. Healthy change is incremental and it emerges through faithfulness. In our sound byte society, we need the discipline to wait for it.

by Chris Horst | Jan 24, 2012 | Blog |

I love a good rags-to-riches story. Sam “Walmart” Walton sold magazines and milked cows in small-town Oklahoma before building the world’s biggest company. Howard Schultz forged his place in American folklore by brewing the coffee shop movement after a hand-to-mouth childhood in Brooklyn’s worst neighborhood. They each made the leap from obscurity to prominence. Mired in adversity, they clawed their way to triumph. But it is a grand charade to suggest that riches alone are better than rags.

Success is a fickle concept. We treat it like a GPS destination. Kick the car in gear, turn right at the T, and pull into the driveway after the rusty garage. Follow this route and you will surely arrive. But success looks nothing like a script. And it can be deceiving. He had everything a man could want or imagine, I muse. But with success, you can’t know it when you see it.

“I’ve gone from village to palace,” exclaimed Ashok Khade. Born in a mud hut without much food, Ashok’s childhood was like a very long walk up a very steep hill. As part of the “untouchables” caste, the lowest of Indian classes, his future was destined to look like his father’s—a grueling life spent cleaning sewers or sweeping streets. But Ashok’s story unfolds just like Sam Walton’s. He studied hard, worked tirelessly and bootstrapped his oil business into a $100M Indian powerhouse.

Ashok arrived. He traded in his rickshaw for a beamer. The oil tycoon now stays at 5-star hotels, adorns his mother with opulent gold jewelry and makes deals with sheiks from Abu Dhabi. The journalist pronounced Ashok’s concluding verdict: “The untouchable boy had become golden, thanks to the newest god in the Indian pantheon: money.”

From a mud shack to the presidential suite, Ashok followed the roadmap to success. And he arrived. He now revels in his wealth, indulging in the finest of luxuries, hoarding his wealth and “living the dream.” But, Ashok has simply gold-plated the chains of poverty.

Ashok should listen to the sage advice of his forbearer. John Rockefeller, also a peasant-turned-oilman, bemoaned, “I have made many millions, but they have brought me no happiness.” At the peak of his success, Rockefeller topped the charts as the wealthiest person in the world. He had no equal. If success were a map, he would be the mapmaker. But, Rockefeller mourned what we are afraid to admit: Success has nothing to do with prosperity. You can indulge in every luxury and still hate waking up in the morning.

Yet we keep peddling the empty promise that a life of prosperity will soothe the wounds of the heart. It won’t. Rockefeller knew it and it shouldn’t surprise Ashok that his newfound riches are like whitewashed tombs.

There is a rags-to-riches story I love more than the rest, however. It is a story of a poor shepherd boy abandoned by his brothers and sold into the hands of a royal Egyptian family. Thrown in jail for years, the poor farmhand persevered and wrote his rags-to-riches story, advancing from the fields to the royal suite.

Pharaoh said to Joseph, “I hereby put you in charge of the whole land of Egypt.” Then Pharaoh took his signet ring from his finger and put it on Joseph’s finger. He dressed him in robes of fine linen and put a gold chain around his neck. He had him ride in a chariot as his second-in-command. – Genesis 41:41-43

From sheering sheep to gracing the throne of the modern world, it was in ancient Egypt where we see rags-to-riches in its purest form. Joseph knew he was not blessed simply to surround himself with frond-waving servants and Egyptian delicacies. He was blessed to bless. “And all the world came to Egypt to buy grain from Joseph, because the famine was severe everywhere.” (vs. 57) It was from this position of power and wealth that Joseph rescued the whole world on the brink of collapse. From poverty to generosity: A true rags-to-riches story.

by Chris Horst | Oct 4, 2011 | Blog |

Over the past eight days, I boarded thirteen separate flights as I hopped across the Asian continent. I spent the most time in India. Actually, I spent time in “both Indias,” a phrase my Indian friends used. I visited the skyscraper-heavy financial district in Mumbai and met families in slums nearby. I drove past the most expensive house in the world and walked through one of the world’s poorest shantytowns. Both Indias.

As a connoisseur of fine airlines (e.g., Southwest, my favorite), India’s airlines impressed me. I flew Jet Airways several times and they did everything right: Prompt departures, quick boarding, no fees, and friendly service. It was hard to believe this upstart airline didn’t exist just seven years ago. Actually, seven years ago, there was only one airline in the country: Air India.

Air India – Source: iFreshNews

Until 2005, the Indian government held a monopolistic stranglehold on the aviation industry. Air India was the only show in town. And it was a really bad show. Prices were sky-high, service was terribly low and Air India consistently lagged in innovation. It is a classic story of government-intervention-gone-wrong.

The real victim of Air India’s failure, however, was the poor. Not only could they not afford to fly, but they also were continually forced to bail out the floundering “business.” As taxpayers, they were on the hook for Air India’s failure. Created under the auspices of “protecting the Indian people,” Air India did exactly the opposite. The vitriol for the company by the people of India is apparent. On my final flight home, I thumbed through the pages of The Telegraph, an Indian newspaper. The editorial title about the airline summarized the country’s sentiment: “A long, sordid and pathetic tale of failure.”

Riddled with inefficiencies and waste, Air India was actually crippled while I was in the country. The entire staff has gone two months without salaries and they were on strike last week. The editorial reviled in the failures of the airline, noting for example, that they recently purchased new planes without doing any price negotiation whatsoever with the manufacturers.

Jet Airways and a handful of other upstart airlines like IndiGo are charting a different and refreshing course, however. Led by aggressive Indian entrepreneurs, these budget airlines deliver on their promise to customers. And, they bring abounding opportunity to the poor. The data doesn’t lie: Since 2005, air traffic in India has tripled, fare prices have dropped dramatically and the quality of service has increased.

I’m an admitted believer in the power of entrepreneurship and the free markets. While not without its warts, I’ve argued that capitalism is the “best broken system” for the most vulnerable in our world. There is a role for government in helping the poor, but Air India illuminates that sometimes the best social service they can do for the poor is unleash the Indian entrepreneur to be the solution. Jet Airways, IndiGo and SpiceJet are up for the challenge; and the world is opening up to low-income Indians as a result. SpiceJet’s motto says it all, “Flying for Everyone.”

by Chris Horst | Jun 21, 2011 | Blog |

The New York Times published a disturbing report. They were clear on the “what” but silent on the “why.” They described an impending disaster, but did not prescribe any solutions. The man is freefalling without a parachute, they figuratively said, but they don’t know why he jumped or how to get him a parachute. They just know he’s falling. Fast.

The disaster is this: Eight million Indian girls were eliminated over the past 30 years because parents preferred boys to girls. Eight million people live in the state of Virginia. Eight million people inhabit Switzerland. Eight million Indian girls never reached their first birthday because they were girls. The fuel for this killing machine? Prosperity.

India’s increasing wealth and improving literacy are apparently contributing to a national crisis of “missing girls,” with the number of sex-selective abortions up sharply among more affluent, educated families during the past two decades, according to a new study…women from higher-income, better-educated families were far more likely than poorer women to abort a girl.

Incomes are increasing dramatically! …and parents can now afford ultrasounds to abort their girls. More Indian parents can read! …and their daughters will never reach kindergarten. People are educated! …and the world will never know the names of eight million girls.

We throw huge concerts to help the poor. We buy fair trade jewelry from global artisans. We petition our lawmakers to preserve foreign aid budgets. We travel to Africa on mission trips. We help the unfortunate to prosper. And for what? For this? Eight million silenced girls? Is this the goal of our attempts to help the vulnerable? To see them prosper and then choose to kill off the babies who lost the gender lottery?

We solve the problems of poverty and introduce the problems of prosperity. The New York Times lacked answers. They broke the news, but the story ends depressingly: “The problem has accelerated.” Apparently, this tragedy is at its genesis.

We need to fill hungry bellies and create jobs. We need to build houses and teach phonics. We are commanded to drill wells and bandage the wounded. However.

Jesus does not want us to stop there. You can own the whole world yet still have nothing, he said. These actions alone are not enough. Apart from the saving grace of Christ, prosperity produces new types of pain. Increased incomes means eight million less Indian girls. You won’t read it in the New York Times, but without Christ, our “giving back” is incomplete. If hearts don’t change; we create new disasters while we solve others.

—————————

The study estimated that 4-12 million girls (I used 8 as an estimate) have been aborted in India over the past 30 years. A different global study estimates that 163 million female babies have been aborted over the past 30 years by parents seeking sons.